By Lucia Pizzaro

(permission granted for publication)

Jewish Liberation Theology Institute

Are you attending or hosting a Seder tomorrow?

The Seder is a festive ritual meal. “Seder” is a Hebrew word that means “order.” The ritual meal is called the “Seder” because it is done in a certain order. The Seder is central to the celebration of the Passover holiday.

Central to the Seder is the book we know of as the “Haggadah,” which translates as “the telling.” And it means to direct us on what we are meant to do around that table. Last week I began to tell you that, even though the Haggadah professes to be the telling of the story of the Exodus, almost none of the verses from the story of the Exodus as recounted in the Torah, actually appear in it. In fact, the re-telling that the Haggadah facilitates is based on another re-telling. So I wanted to give you a closer look at the actual verses that the Haggadah picked to re-tell the story.

According to the Haggadah, the Seder follows these prescribed 14 steps:

Kaddesh (the Kiddush)

Ur’chatz (“washing” of the hands)

Karpas (eating the “herbs” dipped in saltwater)

Yachatz (“dividing” the middle matzah)

Maggid (the “narration”)

Rachtzah (“washing” the hands for the meal)

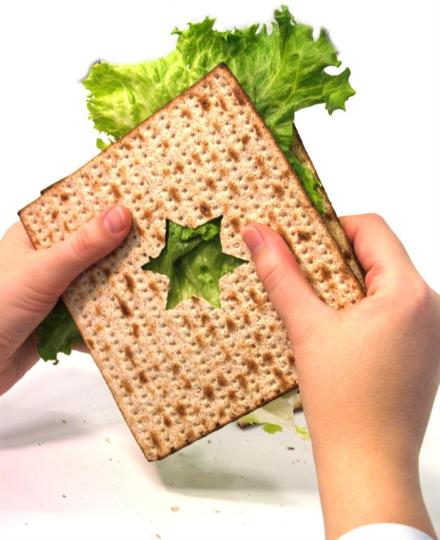

Motzi Matzah (the “benediction” over the matzah)

Maror (eating the “bitter herbs”)

Korech (eating “bitter herbs with matzah”)

Shulchan Orech (the “meal”)

Tzafun (eating of the afikoman – the “last matzah”)

Bareich (“Grace after Meals”)

Hallel (songs of praise)

Nirtzah (the closing formula)

Maggid (the “narration”) is the centerpiece of the entire ritual. Maggid is a Hebrew word that translates into “narration,” and it is the heart of the Haggadah; the main storytelling portion of the Seder.

The Maggid section is filled with many many biblical verses, and it is often difficult to understand in which way the Maggid is enriching us. But the central text that the rabbis of the Mishnah chose to re-tell the story of the Exodus in the Maggid section is a short formula that was used when the Israelites went up to Jerusalem for the presentation of their first fruits:

And the priest shall take the basket from your hand and lay it down before the altar of the LORD your God. And you shall speak out and say before the LORD your God: “My father was an Aramean about to perish, and he went down to Egypt, and he sojourned there with a few people, and he became there a great and mighty and multitudinous nation. And the Egyptians did evil to us and abused us and set upon us hard labor. And we cried out to the LORD God of our fathers, and the LORD heard our voice and saw our abuse and our trouble and our oppression. And the LORD brought us out from Egypt with a strong hand and with an outstretched arm and with great terror and with signs and with portents. And He brought us to this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. And now, look, I have brought the first yield of the fruit of the soil that You gave me, LORD.” And you shall lay it down before the LORD your God, and you shall bow before the LORD your God (Deuteronomy 26:4-10).

I have highlighted the actual formula to be recited when the Israelites went up to Jerusalem for the presentation of their first fruits. When the rabbis chose these verses to be the basis of the re-telling of the story of Exodus at the Seder, the Israelites were no longer bringing their first fruits to the Temple, because the Temple had been destroyed.

By now you may be wondering: Why did the rabbis choose Deuteronomy 26 as the central text of the Seder? Why this text and not any other? Why not use the stories themselves from Exodus?

As is often the case. We don’t have answers. However, we can embark on a few guesses:

These verses are the shortest version in the Torah of the Exodus story; they express gratitude to God for liberating our ancestors from Egypt; it could also be out of an attempt to remember the past (IF indeed this is what happened in the past).

Our Haggadah follows the practice of the Pumbedita and Sura academies of Babylon and it was adopted by all the Jewish communities in the Diaspora. This Haggadah completely superseded the ancient Palestinian version which differed from it in certain respects. There are some Haggadot that were found in Geniza, that follow the Palestinian version, but this tradition eventually disappeared.

So, the Mishnah prescribes that we must recite the formula found in Deuteronomy 26 for bringing our first fruits to the Temple, and the ancient Haggadot that followed the Palestinian tradition included verse 9, “And He brought us to this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey,“ but our traditional (Babylonian) Haggadah ends the story with verse 8: “And the LORD brought us out from Egypt with a strong hand and with an outstretched arm and with great terror and with signs and with portents.”

This is how the Mishnah introduces the prescription that we must recite the formula found in Deuteronomy 26 for bringing our first fruits to the Temple: “He begins with disgrace and ends with praise. And they expound upon “My father was a wandering Aramean” until he finishes the whole portion” (Mishnah Pesachim 10:4). The whole portion!

The Haggadah that we have been using for more than a thousand years leaves out the verse that gives thanks for God giving us “this land.” And that’s not all. The Haggadot that followed the Palestinian tradition interpret the opening word “Aramean” as referring to “our father Jacob.” And thus the disgrace that the Mishnah talks about in its prescription is leaving the land and going to Egypt. And by including verse 9, “And God brought us to this place and gave us this land,” the praise that the MIshnah talks about in its prescription is returning to the land.

On the other hand, however, the Babylonian tradition, which is the tradition that we inherited, and the one that our Haggadot follow, leaves out verse 9 and reinterprets the word “Aramean” to mean not Jacob but Lavan (Jacob’s father in law), so that the formula becomes “Lavan sought to destroy our father Jacob”! In this way, the disgrace is no longer leaving the land of Israel. Rather than a story about leaving the land and coming back to the land, our Haggadah puts forward a story in which slavery and oppression become the disgrace, and liberation the praise. Our Haggadah tells a story from slavery and oppression to liberation. In this way, our Haggadah is an affirmation of Diaspora Judaism.